Digitally Exposed: Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence in Bangladesh – Trends, Cases, and Recommendations

Technical Guidance

Ahmed Swapan Mahmud

Supervised and Edited by

Musharrat Mahera

Analysis and Report

Promiti Prova Chowdhury

Published by

Voices for Interactive Choice and Empowerment (VOICE)

House 35, Block-Ka, Pisciculture Housing Society, Shyamoli, Dhaka 1207, Bangladesh

Contact: [email protected]; Website: www.voicebd.org; Phone: +88-02-58150588

Published in

March 2025

Copyright©

Voices for Interactive Choice and Empowerment (VOICE)

Any part of the publication can be used with proper citation and acknowledgement. The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in the report are strictly based on media monitoring led by VOICE.

This publication is developed under the project titled “Promoting Women’s Equality and Rights (POWER)” supported by Association of Progressive Communications (APC/SIDA).

| TFGBV | Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| GBV | Gender-Based Violence |

| OGBV | Online Gender-Based Violence |

| GSMA | Global System for Mobile Communications Association |

| PCSW | Police Cyber Support Centre for Women |

| UNFPA | United Nations Population Fund |

| LGBTQIA+ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex, asexual, and the + holds space for the expanding and new understanding of different parts of the very diverse gender and sexual identities |

Executive Summary

Online violence against women in Bangladesh has become a significant issue, reflecting deep-rooted gender inequalities in society. This violence, often referred to as Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence (TFGBV), encompasses a wide range of harmful behaviours such as cyberbullying, trolling, revenge porn, online stalking, and threats of sexual violence. Women, especially those who actively engage in public discourse, especially activists, professionals, and journalists, are disproportionately affected. TFGBV in Bangladesh is frequently rooted in misogyny and gender-based discrimination, which escalates in the digital space due to the anonymity that the internet provides perpetrators.

This paper presents 16 cases tracked since October 2024 to provide an in-depth analysis of the various forms of online violence that women in Bangladesh encounter on a daily basis, the socio-cultural context in which such violence persists, the challenges in addressing it, and potential strategies for mitigation. Voices for Interactive Choice and Empowerment (VOICE), a research and advocacy organisation, has developed this paper as part of its project Promoting Women’s Equality and Rights (POWER) supported by Association of Progressive Communications (APC/SIDA). This paper sheds light on the alarming rise and evolving nature of Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence (TFGBV) in Bangladesh, drawing on extensive media monitoring and case tracking. Through systematic observation of newspapers, TV reports, and social media platforms like Facebook, TikTok, YouTube, and X, VOICE has compiled a comprehensive analysis of how digital spaces have become breeding grounds for gendered violence.

The cases documented in this study reveal the multifaceted and deeply troubling forms of TFGBV. These include the proliferation of fake IDs used to impersonate, harass, and defame women; the non-consensual sharing and creation of pornographic content; the spread of misinformation designed to damage reputations and incite violence; and the surge of online hate speech targeting women and marginalised communities. Particularly disturbing is the way online violence often escalates into physical harm, with documented instances of online harassment culminating in real-world assaults, suicide and even femicide.

Moreover, this paper highlights the systemic use of digital spaces to shame, blame, and silence women, particularly those who are activists and vocal about their work and ideologies. Women who challenge societal norms and advocate for human rights frequently become targets of coordinated hate campaigns, facing threats that endanger their safety and well-being. The emergence of deepfakes, manipulated digital content aimed at discrediting and humiliating women and the rise of hate speech targeting LGBTQIA+ communities further exacerbate this digital hostility. Irresponsible and gender-biased media reporting often compounds these issues, perpetuating harmful stereotypes and undermining efforts to combat TFGBV.

In addition to documenting these cases, the paper examines the existing legal frameworks relevant to TFGBV in Bangladesh, identifying gaps in enforcement and accessibility. Prior to writing this paper, VOICE hold an advocacy workshop bringing together journalists, civil society representatives, human rights activists, academicians, and legal support organisations to address TFGBV and propose actionable solutions. Key recommendations included strengthening legal frameworks to address cyber harassment and online exploitation, with faster judicial processes and stronger protections for victims, especially marginalized groups like LGBTQIA+ individuals and indigenous women. Training law enforcement and legal professionals on digital crimes, gender sensitivity, and forensic technology was emphasized to improve investigations and accountability.

Enhancing digital literacy through school curriculums and awareness campaigns was proposed to promote responsible online behaviour. Participants also called for better victim support through user-friendly reporting mechanisms, rapid legal aid, and counselling services. Holding digital platforms accountable for content moderation and pushing for stronger data protection laws were deemed essential. Cultural reforms, including gender-sensitivity training and challenging patriarchal norms, were highlighted to address the root causes of TFGBV.

Finally, the paper argues that addressing TFGBV is crucial for achieving SDGs. TFGBV undermines women’s rights, silences their voices in democratic processes, and limits their participation in society, while also hindering access to technology and ICTs. Addressing TFGBV is crucial not only for protecting women’s rights but also for fostering inclusive participation, promoting justice, and ensuring a safer, more equitable digital world for all.

Nuances of Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence

As per the definition of United Nations Population Fund, TFGBV refers to acts of violence committed, assisted, aggravated, or amplified through information and communication technologies or digital media, targeting individuals based on their gender.[1]

Key Characteristics of TFGBV:

- Anonymity: Perpetrators can conceal their identities, making accountability challenging.

- Remote Perpetration: Offenders can inflict harm from a distance without physical proximity.

- Accessibility: Digital tools are readily available and affordable, lowering barriers for perpetrators.

- Automation: Technology enables automated attacks, increasing the scale and frequency of abuse.

- Persistence: Harmful content can be difficult to remove, causing long-term distress.

- Collective Organization: Groups can coordinate attacks, intensifying the impact on victims.

- Impunity: Lack of comprehensive legal frameworks often leaves perpetrators unpunished.

- Normalization: Such violence contributes to the societal acceptance of abuse against women and girls.

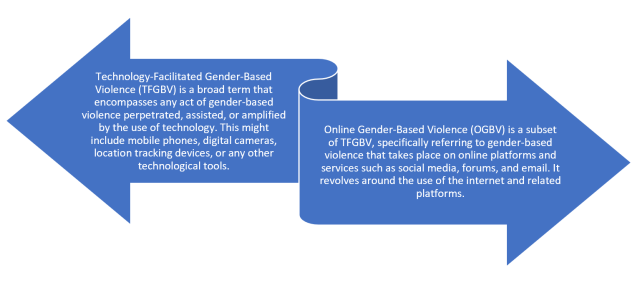

In the digital age, gender-based violence (GBV) has transcended physical barriers, manifesting itself in novel ways on various technological platforms. Two commonly referred terms that we come across are “Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence” and “online gender-based violence.”[2] While they might seem synonymous at first glance, delving deeper into their implications and manifestations reveals their distinct characteristics.

Figure 1: Definitions of TFGBV and OGBV

TFGBV: The scope of TFGBV can range from using technology to stalk someone (e.g., using location tracking devices) to blackmail (e.g., threatening to leak personal videos or photos). It is a spectrum that includes digital harassment as well as offline acts that are facilitated through technology.

OGBV: OGBV primarily focuses on digital spaces. Examples include online stalking, cyberbullying based on gender, doxing (publicly releasing private information), and sharing intimate images without consent. These acts may not always have a direct offline component, but their repercussions can spill into the offline world. Certain cybercrimes disproportionately target women, including:

- Online Harassment: Unwanted messages, comments, or threats.

- Cyberstalking: Persistent tracking and monitoring online activities.

- Image-Based Abuse: Non-consensual sharing of intimate images, including deepfakes.

- Sextortion: Blackmail involving sexual information or images.

- Doxing: Public release of private personal information.

- Impersonation: Unauthorised use of someone’s identity online.

- Hate Speech and Defamation: Spreading harmful false information or offensive content.

- Technological Control: Restricting or monitoring someone’s use of technology.

Violence Against Women Through Digital Technology: The Bangladesh Context

In the 2023 Global Gender Gap Report published by the World Economic Forum, Bangladesh ranked 59th out of 146 countries and held the top position in South Asia for the ninth consecutive year. However, the reality presents a different picture when it comes to gender-based violence, particularly violence against women through digital technology. These incidents largely go unreported, making them difficult to address.

Digital harassment not only causes physical and psychological harm to women but is also used as a tool to control and intimidate them. Due to social stigma and fear of shame, many women choose silence over seeking justice.

A global report has found that women are lagging behind men in Bangladesh in both mobile ownership and mobile internet adoption.

In Bangladesh, 85 percent of adult males own a mobile phone, compared to 68 percent of adult females. Mobile internet adoption rates are 40 percent for men and only 24 percent for women, as per the report titled “The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2024.” The Global System for Mobile Communications Association (GSMA), a global organization of mobile phone service providers, published the report in May last year. GSMA published data on 12 low- and middle-income countries.

According to the survey, Bangladesh has the highest gender gap in mobile internet adoption among Asian countries at 40 percent. In comparison, the gap is 30 percent in India, 38 percent in Pakistan, and 8 percent in Indonesia. Women in Bangladesh are also falling behind in smartphone ownership. While 40 percent of men own a smartphone, only 22 percent of women have one.[3]

Despite lower internet usage among women, online violence remains prevalent both in digital spaces and in real life.

To combat cyber harassment against women, the Bangladesh Police launched the Cyber Support for Women initiative in 2020[4]. From then until May 2024, a total of 60,808 women have sought assistance from this service. The nature of complaints includes: 41% related to doxing (personal data leaks), 18% Facebook account hacking, 17% blackmailing, 9% impersonation, 8% cyberbullying. Many victims are unsure where to report these crimes or how to seek help. Initially, they hesitate to inform their guardians or trusted individuals, further worsening their situation.

The psychological toll of TFGBV is profound, with victims often suffering in silence due to fear, shame, and social stigma. The impact extends into their offline lives, affecting mental health, relationships, education, and livelihoods. Despite initiatives like the Cyber Support for Women service, many women remain unaware of resources or too afraid to seek help. TFGBV is not an isolated issue but part of a larger pattern of gender-based oppression. As technology continues to evolve, so must our understanding of its potential to cause harm. The following section will highlight the lived experiences of TFGBV victims in Bangladesh, shedding light on the severe consequences they face.

Cases of TFGBV in Bangladesh

Women who engage in public discourse, particularly activists, professionals, and journalists, are often disproportionately targeted by TFGBV in Bangladesh. This form of violence is deeply rooted in societal misogyny and gender-based discrimination, both of which are amplified in the digital space where anonymity emboldens perpetrators. The cases documented below have been tracked since October 2024, offering a closer look at the diverse forms of online violence faced by women in Bangladesh. These case studies shed light on the social and cultural conditions that enable such abuse, the barriers to seeking justice, and the severe personal and professional consequences for victims. Through these real-life accounts, we aim to deepen understanding of the evolving nature of TFGBV and the urgent need for responsive measures. The cases have been categorised as per the types of online violence i.e. revenge porn, manipulated pornographic image, deepfake, online threats and hate speech, and gendered disinformation.

The tragic consequence of online exploitation in Dhaka

In January 2025, a tragic incident in Dhaka, Bangladesh, highlighted the perils of online interactions and underscored significant societal and law enforcement challenges. A teenage girl, a student from South Dakkhin Khan, went missing on January 16 after informing her parents she was going shopping. Subsequent investigations revealed she had been lured to an apartment in Mohakhali by individuals she met online. There, five men allegedly bound, assaulted, and ultimately killed her. To conceal the crime, they disposed of her body in the Hatirjheel lake. On February 2, authorities recovered her decomposed remains. Two suspects, Robin and Rabbi Mridha, were apprehended and reportedly confessed to their involvement. This case underscores the urgent need for public awareness regarding the dangers of online interactions, especially among vulnerable groups like teenagers. It also emphasises the necessity for robust law enforcement measures to monitor and prevent such heinous crimes, ensuring the safety and security of all citizens.

Type of Violation: Crime following online introduction

Source: Jago News [Link: https://rb.gy/iiozux]

Date of documentation: 22 February 2025

Footballer Sumaya receives death and rape threats

In February 2025, Matsushima Sumaya, a distinguished member of Bangladesh’s SAFF Women’s Championship-winning football team, publicly disclosed severe instances of online harassment. Following her vocal criticism of national team coach Peter James Butler, Sumaya became the target of numerous death and rape threats via social media platforms. She revealed that her commitment to football, which involved overcoming familial opposition and prioritising her athletic career over personal and educational pursuits, had culminated in a distressing reality of cyber abuse. The psychological impact of these threats was profound, leaving her in a state of trauma and regret. This incident underscores the pervasive issue of TFGBV in Bangladesh, highlighting the urgent need for protective measures for women in digital spaces. The Bangladesh Football Federation initiated an investigation into the players’ grievances against the coach, with findings anticipated later that month.

Type of Violation: Online threats

Source: bdnews24.com [Link: https://bdnews24.com/sport/42399da7506b]

Date of documentation: 5 Feb 2025

False AI-generated image targets Syeda Rizwana Hasan and Mehazabien

A fabricated and degrading narrative has emerged involving Syeda Rizwana Hasan, the Forest and Environment Advisor, and Mehazabien Chowdhury, a renowned Bangladeshi actress and model. An AI-generated photocard falsely depicts Mehazabien in an absurd scenario, wearing a dress made from ‘environmentally friendly condoms’. The altered image, paired with a humiliating caption, seems aimed at tarnishing the reputations of both individuals. In the fabricated narrative, Advisor Rizwana is wrongfully portrayed as endorsing this bizarre and inappropriate use of condoms, adding to the absurdity and harm of the content. The intent behind this manipulation is clear: to degrade and ridicule both the celebrity and the environmental advocate. Such misleading content, driven by technology, highlights the growing dangers of AI manipulation in the media. It raises serious concerns about the spread of false narratives that target public figures, potentially causing lasting damage to their personal and professional lives. In this case, the combination of celebrity culture and environmental advocacy has been used to create a shameful and harmful portrayal, revealing the need for greater vigilance and responsibility in media representation.

Type of Violation: Deepfake/misinformation

Source: Fact Watch [Link: https://perma.cc/KK6Z-YPA2]

Date of documentation: 12 Feb 2025

DU student withdraws harassment case amid ‘rape, death threats’

In March 2025, a female student at Dhaka University (DU) reported being verbally harassed by Mostafa Asif, an assistant bookbinder at the university library, regarding her attire. The incident occurred near the Raju Memorial Sculpture, where Asif allegedly criticized the student’s dress and made inappropriate comments. After the student attempted to involve the university proctor, Asif fled the scene. She subsequently shared her experience on Facebook, including a photograph of Asif, which garnered significant attention and led to demands for action within the university community. The university administration identified Asif and handed him over to Shahbagh police, leading to his arrest. However, following his detention, a group identifying themselves as “Towhidi Janata” gathered outside the police station, demanding his release. After Asif was granted bail by a Dhaka court, the student began receiving death and rape threats online, which led her to withdraw the case. She expressed frustration with the police, alleging that they had disclosed her personal information, further compromising her safety. This case highlights significant concerns regarding victim safety, the judicial process, and the prevalence of online harassment in Bangladesh. It underscores the challenges individuals face when reporting harassment and the urgent need for robust mechanisms to protect and support victims throughout the legal process.

Type of Violation: Online Threat and Hate Speech

Source: The Business Standard [Link: https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/du-student-withdraws-harassment-case-amid-threats-1086536]

Date of Documentation: 11 March 2025

Activist Farzana Sithi faces rape threats during Facebook live

In February 2025, Farzana Sithi, an activist known for her role in anti-discrimination movements, became the target of severe online harassment. Content creator Khaled Mahmud Hridoy conducted a Facebook Live session on February 27, during which he allegedly threatened to rape Sithi, criticized her clothing and lifestyle, and encouraged others to assault her. Hridoy even offered rewards for carrying out such actions.

Upon discovering the video, Sithi felt endangered and filed a case against Hridoy at Sher-e-Bangla Nagar Police Station on March 11, 2025, citing threats and defamation. She expressed concern over her safety and highlighted the broader issue of online harassment faced by women. Prior to this incident, Hridoy had been arrested by Savar police for creating and disseminating videos containing inappropriate gestures and comments towards women on social media. Sithi emphasised the necessity of holding individuals accountable for such behaviour to prevent societal disorder. This case underscores the urgent need for stringent measures against online harassment and the protection of individuals advocating for social justice. It highlights the challenges activists face in digital spaces and the importance of legal frameworks to address and deter such misconduct.

Type of Violation: Online Threat and Hate Speech

Source: The Daily Ittefaq [Link: https://rb.gy/wkue1z]

Date of Documentation: 18 March 2025

The Rise of Fake IDs and Pornography

The rise of fake IDs and pornography in Bangladesh is a disturbing trend linked to TFGBV. Predators and cybercriminals exploit social media and messaging apps to create fake profiles, manipulate minors, and spread explicit content without consent. Young girls are particularly vulnerable, facing blackmail, harassment, and long-term psychological trauma. The lack of robust digital literacy and legal safeguards exacerbates the issue, making urgent policy interventions and awareness campaigns necessary to combat online sexual exploitation and ensure children’s safety in the digital space. Few of the cases are narrated below.

SSC candidate arrested in Tangail for alleged involvement in pornography case

In January 2025, a female SSC candidate from Bhunapur Pilot Government High School was arrested for allegedly creating pornographic content using edited images of local teachers, students, and other individuals. These videos were circulated in multiple Messenger groups, followed by demands for large sums of money. Police investigations revealed that Facebook and Gmail accounts—under aliases like “Dilruba” and “Rakibul Islam”—were created using the student’s mobile device. Through collaboration with Facebook and Google, law enforcement traced the activity back to her. Her mobile phone and laptop were seized, and investigators reportedly found proof of content dissemination. However, the accused student and her family have strongly denied the allegations. They claim that the girl’s own photos were misused to fabricate the videos, and money was extorted from them. Two individuals, named Shimanto and Sifat from Mirzapur and Gopalpur, allegedly confessed to the crime but were later released. The case has sparked debate over the protection of minors in digital crimes and the accuracy of digital evidence, raising critical concerns about justice, due process, and the psychological toll of digital harassment on young women.

Type of violation: Deepfake

Source: Desh Rupantor [Link: https://www.deshrupantor.com/]

Date of documentation: 16 Feb 2025

Girl kills herself as ex-husband publishes private images

A 17-year-old girl committed suicide after her ex-husband circulated her private pictures on social media. The perpetrator, Helal Uddin Sarder, created a fake profile of the teenager and started uploading their intimate pictures and videos. The girl poisoned herself In November 2024, a 17-year-old girl from Raninagar Upazila, Naogaon, Bangladesh, tragically ended her life by ingesting poison. This act was reportedly precipitated by her ex-husband, Helal Uddin Sardar, who allegedly disseminated her private photos and videos on social media platforms following their divorce in July 2024. The couple had married in January 2024, but their union was short-lived, culminating in divorce seven months later. Post-divorce, Helal, a Malaysia-based expatriate, is accused of creating fake social media profiles to share intimate content of his former wife. He also allegedly sent these materials directly to her via messaging apps, subjecting her to severe emotional distress. The public exposure and ensuing humiliation reportedly led the young woman to consume poison on the evening of November 4, 2024. Despite being rushed to Naogaon Sadar Hospital, she succumbed to the effects later that night.

Type of violation: revenge porn

Source: newsbangla24.com [link: https://www.newsbangla24.com/news/249504/Accused-of-spreading-private-pictures-against-ex-husband-suicide-of-a-girl-by-drinking-poison]

Date of documentation: 12 Feb 2025

Ex-boyfriend publishes intimate pictures, newly-married girl kills herself

A newly-married girl tried killing herself after her ex-boyfriend shared their intimate pictures with her husband. The perpetrator sent t In November 2024, a tragic incident in Subarnachar, Noakhali, Bangladesh, underscored the devastating impact of Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence (TFGBV). Poppy, a young bride and first-year degree student at Saikat Government College, faced severe emotional distress after her former boyfriend, Mohin Islam Riyad, sent compromising messages and videos to her husband, Abdullah Al Mahmud, a Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) member. This breach of privacy led to accusations from Mahmud and his family, questioning Poppy’s character and expressing intentions to dissolve the marriage. Overwhelmed by the stigma and familial rejection, Poppy attempted suicide on November 20 by hanging herself at a relative’s home. She was initially treated at Noakhali General Hospital and later transferred to a private hospital in Dhaka, where she succumbed to her injuries on November 22. Following her death, Poppy’s uncle filed a case against Riyad, Mahmud, and Mahmud’s family members for abetment to suicide. he images and videos to her husband’s phone. This led to conflict where the husband and his family questioned her character. Following this tension, the girl hung herself and later died in hospital while under treatment.

Type of violation: revenge porn

Source: shomoyeralo.com [Link: https://www.shomoyeralo.com/news/294600]

Date of documentation: 12 Feb 2025

How TFGBV Becomes a Political Tool against Women

During the July 2024 uprising, women played a critical role [i]n advocating for political reforms and social justice, joining protests and voicing their demands both on the streets and online[5]. Young women, particularly students, were at the forefront, organising rallies, sharing real-time updates on social media, and pushing for transparency and accountability in governance. Their participation was not only a call for political change but also a stance for gender equality and women’s rights.

| One woman, who actively participated in the student-people movement, said that her videos were deliberately clipped and manipulated, leading to a flood of hateful comments. Distorted videos about her circulated online, and even her neighbours began harassing her parents.

[Source: Prothom Alo]

|

However, the women involved in this movement were not immune to online violence. As their visibility grew, so did the targeted harassment. The forms of TFGBV they faced included sexualised threats, doxxing (revealing private information), and the circulation of intimate photos or videos without consent, aimed at silencing their activism. This online abuse was not just an attack on their voices but also an attempt to discredit their efforts and intimidate other women from participating in the political discourse.

According to the Police PCSW, a total of 9,117 cyber harassment complaints were recorded in 2024. The highest number of complaints came in September (979) and October (881), notably following the major movement, suggesting a possible correlation between increased online visibility and targeted harassment. The monthly breakdown is as follows:

| Month | Number of Complaints |

| January | 715 |

| February | 653 |

| March | 723 |

| April | 730 |

| May | 773 |

| June | 842 |

| July | 710 |

| August | 630 |

| September | 979 |

| October | 881 |

| November | 714 |

| December | 767 |

Figure 2: Monthly number of cases filed at PCSW

False propaganda targets anti-discrimination leader Nusrat Tabassum

A recent wave of online harassment has targeted Nusrat Tabassum, a central executive committee member of the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement and a student of Dhaka University’s Department of Political Science. A video, falsely claimed to be a “leaked secret video of Coordinator Nusrat,” has gone viral on social media, accompanied by malicious captions such as “Bedi Coordinator Nusrat Tabassum is finished” and “Bedi Coordinator Nusrat Tabassum gifted the nation 3 minutes and 12 seconds.” These derogatory texts have fuelled a smear campaign against her, aiming to tarnish her reputation and undermine her activism. Upon investigation, Rumour Scanner found that the video in question had been circulating online since 2022 and did not feature Nusrat Tabassum. The video, which was being presented as a recent leak, was revealed to have no connection to her, debunking the false claims. The spread of this disinformation highlights the growing challenges activists face in the digital age, where online harassment and defamation are often used as tools to silence voices of dissent. Nusrat Tabassum has yet to publicly respond to the smear campaign, but the incident underscores the need for vigilance against the harmful effects of fake news and online abuse.

Type of Violation: Manipulated pornographic image

Source: Rumour Scanner [Link: https://rumorscanner.com/fact-check/coordinator-nusrat-tabassum-fake-video/136350]

Date of documentation: 11 Feb 2025

False propaganda targets anti-discrimination leader Ishita Zaman Dolly

In early February 2025, a series of explicit images featuring an unidentified young woman surfaced on social media platforms in Bangladesh. These images were accompanied by claims that they depicted Ishita Jaman Dolly, a coordinator of the anti-discrimination student movement from Faridpur’s Boalmari region. However, upon investigation by Rumor Scanner, it was determined that the images did not feature Ms. Jaman Dolly. Instead, they were photographs of Payel Mondal, a model based in Kolkata, India. Reverse image searches traced these images to Ms. Mondal’s verified Facebook profile, where they had been posted at various times. This incident highlights the vulnerability of individuals, especially women, to the misuse of their images in digital spaces. Such actions not only infringe upon personal privacy but also have the potential to harm reputations and incite unwarranted controversy.

Type of Violation: Manipulated pornographic image

Source: Rumour Scanner [Link: https://rumorscanner.com/fact-check/indian-models-photo-claimed-as-coordinators-photo/138743]

Date of documentation: 12 Feb 2025

Distorted image goes viral using the name of advisor Rizwana Hasan

In early 2025, a digitally altered image of Syeda Rizwana Hasan, an advisor to Bangladesh’s Ministry of Water Resources and Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, surfaced on Facebook. The manipulated image depicted her in a compromising position, leading to widespread circulation and public scrutiny. Fact-Watch’s investigation revealed that the original photograph originated from an adult website, where a different woman’s image was edited to feature Rizwana’s face. This manipulation was primarily disseminated through a Facebook account named “Chemical Ali”, known for sharing similar doctored images of prominent women. This incident mirrors a broader pattern of digital harassment targeting female public figures in Bangladesh. For instance, in December 2024, a fabricated quote attributed to Rizwana appeared on a fake Kalbela magazine card, falsely suggesting her criticism of condom usage. Such instances highlight the misuse of digital platforms to spread misinformation and defame women in positions of authority. These events underscore the urgent need for robust measures to combat Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence in Bangladesh. The deliberate distortion and dissemination of women’s images not only violate their privacy but also perpetuate harmful gender stereotypes and societal biases.

Type of Violation: Manipulated pornographic image

Source: Fact Watch [Link: https://www.fact-watch.org/adviser-rizwana-hasan-altered-image-viral/]

Date of documentation: 12 Feb 2025

Deepfake scandal involving press secretary’s daughter sparks outrage

A disturbing case of deepfake manipulation has emerged, involving the daughter of Press Secretary Shafiqul Alam. The incident centres around doctored images that went viral, showing the public figure’s daughter in explicit content. The manipulated images were created by replacing the face of a porn actor with that of the Press Secretary’s daughter, a blatant attempt at character assassination. The incident has raised alarm among both the public and authorities, highlighting the growing menace of AI-generated image manipulation and its potential to cause irreparable damage to individuals’ reputations. Fact Watch, an organisation dedicated to combating misinformation, has confirmed that the images circulating online were heavily doctored, exposing the malicious use of deepfake technology for spreading falsehoods. This case has sparked outrage, with many questioning the ethics and accountability of individuals behind such content. It has also underscored the increasing vulnerability of public figures and their families to such attacks in the digital age. Authorities are investigating the matter, with calls for stricter regulation of AI manipulation and measures to protect individuals from online character assassination. As the case unfolds, it serves as a stark reminder of the dangers posed by digital misinformation.

Type of Violation: Manipulated pornographic Image

Source: Fact Watch [Link: https://www.fact-watch.org/press-secretary-daughter-altered-photo]

Date of documentation: 04 Feb 2025

Misattribution of images to actress Sabnam Faria

In December 2024, images purportedly depicting Bangladeshi actress Sabnam Faria circulated on social media, accompanied by captions suggesting her personal relationships with an individual. Upon investigation, Rumour Scanner, a fact-checking organisation, determined that the images were not of Sabnam Faria. The photos actually featured Indian actress Poonam Bajwa, as evidenced by matching images found on Bajwa’s Instagram account. Additionally, Sabnam Faria’s official Facebook page did not contain such images. The caption with the distorted images described Faria as lal biplobi or Red Rebel. During the July Movement in Bangladesh, many uploaded a red profile picture (DP) on social media, a gesture that was part of a broader trend during the movement. The colour red symbolised solidarity with the protesters and their demands for political change. Thus, circulation of such images and captions seems to make Faria a target of online smear campaigns, insinuated her political stance.

Type of violation: Deepfake

Source: Rumour Scanner [Link: https://rumorscanner.com/fact-check/altered-picture-of-sabnam-faria]

Date of documentation: 12 Feb 2025

Circular claiming Puja Cherry as advisor to ‘Chhatra Shibir women wing’ surfaces across social media

A false circular last year circulated on social media, attributed to the women’s wing of Bangladesh Islami Chhatra Shibir, the student organisation linked to the Jamaat-e-Islami political party. The circular falsely claimed that popular Bangladeshi actress Puja Cherry had been appointed as the law and human rights advisor for the group’s “non-Muslim” wing. The misleading claim quickly gained traction, causing confusion and concern among social media users. In response, Puja Cherry took to social media to firmly deny the allegation, labelling it as a rumour. She emphasised that she had no association with the position or the organisation, aiming to protect her reputation and distance herself from the false claim. Fact-checking organisations and media outlets scrutinised the circular, exposing it as a fake. They highlighted several inconsistencies, such as the use of unofficial language and the absence of credible sources, casting doubt on its authenticity. These fact-checkers urged caution when sharing unverified information, particularly in the era of widespread digital misinformation. Monjurul Islam, president of Bangladesh Islami Chhatra Shibir, also publicly refuted the rumour, declaring the claim completely baseless and dismissing it as an attempt to sow confusion. This incident underscores the critical need for careful fact-checking in the digital age.

Type of Violation: Gendered Disinformation

Source: Somoy Entertainment [Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EJ4akM7LweI]

Date of documentation: 10 Feb 2025

Online Hate Speech and Biased Media Representations: An Interconnected Issue

In Bangladesh, hate speech targeting women and LGBTQIA+ communities have become a pervasive issue, exacerbated by certain online platforms and media portrayals that reinforce harmful stereotypes. This environment not only marginalises these groups but also perpetuates societal biases, hindering progress toward equality. Social media platforms have become breeding grounds for hate speech against women and LGBTQIA+ individuals. Groups like “Feminism is Cancer”[6] on Facebook actively disseminate misogynistic content, aiming to undermine feminist movements and silence women’s voices. These groups perpetuate narratives that feminism is detrimental to societal values, thereby discouraging discussions on gender equality. In 2023, transgender rights activist Ho Chi Minh Islam was set to speak at a career fest at North South University but was forced to step down following protests from a group of students. Last year, Asif Mahtab Utsha, a former part-time teacher at BRAC University, sparked debate when he criticised a seventh-grade textbook’s inclusion of gender-diverse communities and tore pages from the book during a discussion at Dhaka’s Institute of Diploma Engineers. Following Mahtab’s statements and activities going viral, Ho Chi Minh Islam told BBC Bangla that their community now feels more threatened than ever[7]. That such social media-driven propaganda fosters confusion, especially around concepts like transgender identity and homosexuality, which are often mistakenly conflated.

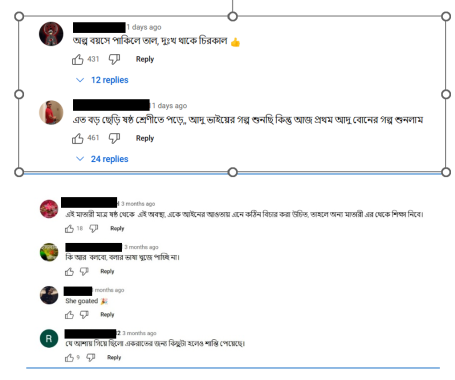

11-year-old girl trolled following media reports

The recent media coverage of the rescue of a missing child from Dhaka’s Adabor has raised serious concerns about the lack of adherence to child protection laws. Both the law enforcement officials and journalists failed miserably to protect the child’s best interest. The child was seen being interrogated by police personnel in the midst of a crowd. It was a clear violation of a child’s right to privacy by every standard. Moreover, lack of media literacy and internet etiquette have made the cyberspace in Bangladesh dangerous for everyone, but particularly for children and women. Below are some comments found on the questionable news piece on YouTube.

Source: ATN News [Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9niLg54L7QM]

Date of documentation: 16 February 2025

Mala Khan goes vocal against ‘false accusations’

Scientists, officers, and employees of the Bangladesh Reference Institute for Chemical Measurements were recently vocal against their former chief scientific officer Mala Khan, accusing her of threats, abductions, and filing false cases to harass her colleagues. However, some media reports focused more on her private affairs and relationships are not only stirring online hatred but also peril offline, Mala has claimed[8]. In a press conference she said her pictures along with the allegations have become widespread in social media and the situation has created ‘social barriers’ for her. As example, she said that recently she was intercepted by a group of people at a shop who asked explanations from her. Such incidents are ruining her life and career, she has told the media.

Source: ATN News [Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ipq0A-eKsV0]

Date of documentation: 13 February 2025

Example of Online Hate Speech

The following screenshots serve as examples of the derogatory comments commonly encountered in social media interactions or news coverage involving female celebrities in Bangladesh. Here we take a look into comments hurled at Porimoni, a popular Bangladeshi actress, and Taslima Nasrin, a prominent author frequently targeted for her controversial views on gender inequality, religious intolerance, and women’s rights.

These comments often reflect a deeply ingrained culture of online harassment, where women in the public eye are subjected to sexist, judgmental, and inflammatory remarks. To maintain privacy and protect individuals’ identities, the names of the commenters have been deliberately blurred.

This type of online abuse is emblematic of the broader challenges faced by female public figures, who are frequently targeted for their personal lives, professional choices, and public statements. For celebrities like, Porimoni and Taslima Nasrin, whose actions or opinions often spark controversy, these comments highlight the pervasive nature of gender-based online violence. Such behaviour underscores the urgent need for enhanced media literacy, accountability, and measures to curb online harassment, especially in Bangladesh’s social media landscape.

The cases mentioned above are testament that TFGBV is not just a tool for silencing women but also a potent means of spreading misinformation. During periods of political unrest or conflict, online harassment is weaponised to discredit women activists, journalists, and leaders through the circulation of false narratives, deepfakes, and manipulated content. Extremist groups and political actors exploit TFGBV to amplify misogynistic ideologies, undermining women’s credibility and distorting public perception. False accusations, doctored images, and fabricated scandals not only cause personal harm but also erode trust in democratic discourse. By amplifying misinformation through coordinated attacks, TFGBV becomes a means of social control, actively discouraging women from engaging in public and political spaces.

Despite the severity of TFGBV, which has become a widespread and alarming phenomenon, many victims remain unsupported, and the perpetrators often escape punishment. Let’s examine the existing laws in more detail to better understand these challenges.

Existing Laws in Bangladesh for Women’s Protection in Cyberspace

In Bangladesh, the legal framework for protecting women and children from online and digital harm has evolved over time, though challenges remain in addressing the growing concerns of TFGBV. Several laws have been enacted to safeguard women from harassment, defamation, and exploitation, including specific provisions addressing offenses committed through digital platforms. These laws, while significant, often require further clarity and enforcement to effectively address the unique nature of cybercrimes. Below is an overview of the existing legal provisions aimed at protecting women and children in cyberspace.

Section 76 of the Dhaka Metropolitan Ordinance states that the punishment for harassing women includes at least one year of imprisonment or a fine of two thousand taka, or both.

Section 500 of the Penal Code describes the punishment for defamation, stating that a person found guilty of this offense may face two years of simple imprisonment, a fine, or both.

Section 8(1) of the Pornography Control Act, 2012 states that if any individual produces pornography, collects participants for production through contracts, coerces or entices any woman, man, or child to participate, or records videos through deception, they can face a maximum of seven years of rigorous imprisonment and a fine of up to two lakh taka. This is a non-bailable offense.

Section 69 of the Bangladesh Telecommunication (Amendment) Act, 2001 makes it a punishable offense for any individual to use telecommunication or radio equipment to send messages that are obscene, threatening, or seriously offensive to others.

Section 10 of the Women and Children Repression Prevention Act, 2000 states that if any person, with the intention of fulfilling their sexual desires, touches any woman or child’s sexual organs or any other body parts using any object or their body, or violates a woman’s modesty, it will be considered sexual harassment. The offender will be sentenced to a minimum of three years and a maximum of ten years of rigorous imprisonment, along with a fine.

In 2009, the High Court Division of Bangladesh issued a guideline verdict on preventing sexual harassment. This ruling primarily provided directives for preventing sexual harassment in educational institutions, workplaces, and all spheres of society. According to this verdict, indecent behaviour can also be considered sexual harassment. The verdict includes various forms of unwelcome sexual conduct, both direct and implied, such as: physical touch or attempts to do so, sexually harassing or derogatory remarks, showing pornography, obscene gestures, sexualized language or comments, following someone persistently, mocking someone using sexually suggestive language

Children Act of 2013: Also known as the Shishu Ain, this law was enacted to implement the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. It criminalizes cruelty to children working in formal and informal sectors. The Act also affirms that it is a punishable criminal offence if any information that directly or indirectly identifies a child involved in a trial is published in any print or electronic media or online.[9]

While older children may be more exposed to cyberbullying than younger ones, children are not immune from harmful content, sexual exploitation and abuse, and cyberbullying. The Children Act of 2013 in Bangladesh addresses child protection, including online violence.

Cyber Protection Ordinance 2024: Claims are ripe that the newly approved Cyber Protection Ordinance-2024 largely neglects minorities, women and children, and the indigenous groups. At a view-exchange meeting recently, Supreme Court lawyer Abdullah Al Noman said the new ordinance fails to address sexual harassment of women and children in the digital space, adding that it does not clearly outline how sensitive issues should be handled or tried.

The Importance of Advocacy

Advocacy plays a crucial role in changing both social perceptions and legal frameworks. By raising awareness among the public, policymakers, and the media about the severity of online violence against women, it is possible to bring about a shift in societal attitudes. In the digital age, ensuring women’s meaningful participation requires more than just strengthening security measures, it necessitates structural changes that challenge the negative gender norms ingrained in society. The following steps are essential for driving the necessary transformation, fostering a comprehensive shift in both societal attitudes and institutional practices.

Raising Public Awareness

Public awareness is a key tool in combating technology-facilitated sexual harassment. To educate people about the different forms of online violence, its impact, and the relevant laws, it is essential to conduct social media campaigns, workshops, and community awareness programs. The voices of survivors must be amplified to highlight the harmful effects of online sexual violence. Additionally, essential information must be made easily accessible to provide support to victims.

Strengthening Digital Security

Women must acquire the knowledge and skills needed to ensure their safety online. Priority should be given to training women human rights activists and female journalists on digital security. These trainings should cover topics such as protecting personal information, securing online accounts, and identifying and countering online threats. Moreover, there should be safe spaces where women can share their experiences, fostering solidarity and collective resistance against digital violence.

Engaging Policymakers

Policymakers must be pressured to enact and enforce laws addressing internet-based sexual harassment. To ensure justice for victims of online violence, cyber laws should explicitly recognize gender-based abuse in digital spaces. Additionally, existing laws must be effectively implemented, and law enforcement agencies should receive proper training to handle such cases.

Recommendations: How to Combat TFGBV

After analysing the pattern of TFGBV in Bangladesh, this paper offers a set of targeted recommendations designed to address the root causes, strengthen legal and institutional frameworks, enhance victim support systems, and promote a culture of digital accountability. These recommendations are grounded in both qualitative and quantitative insights gathered from survivor testimonies, expert interviews, and a review of existing laws and digital safety mechanisms. The aim is not only to respond to incidents of TFGBV but also to prevent them by fostering a safer and more inclusive online environment for all genders. Policy reform, capacity-building for law enforcement, digital literacy initiatives, and multi-stakeholder collaboration form the backbone of these proposed strategies.

Strengthening Legal and Policy Frameworks: Clear and comprehensive legal provisions must address cyber harassment, online sexual exploitation, and digital violence. Judicial processes should be expedited to prevent case withdrawals, with strict penalties for perpetrators and protections for victims. Police accountability mechanisms are essential, and laws must be amended to safeguard marginalized groups, including LGBTQIA+ individuals and indigenous women, from digital abuse.

Capacity Building for Law Enforcement and Legal Professionals: To combat TFGBV effectively, law enforcement must receive comprehensive training on digital crimes, gender sensitivity, and forensic technology. Providing digital forensic tools and expertise will strengthen investigations and prosecutions. Internal oversight mechanisms should eliminate bribery and unofficial settlements. Additionally, officers must be trained in handling digital evidence and collaborating with tech companies to ensure thorough case investigations.

Strengthening Digital Literacy and Ethical Use of Technology: To foster a safer digital environment, schools must integrate digital ethics, online safety, and responsible digital behaviour into their curriculums. Teachers should be trained to identify and address online harassment, equipping students with awareness of digital risks. Additionally, nationwide awareness campaigns targeting youth, parents, and educators are essential to combat TFGBV and promote responsible online engagement.

Enhancing Victim Support and Reporting Mechanisms: To address online harassment, clear intervention procedures must be put in place, especially in cases with an imminent threat of offline violence or psychological harm. User-friendly reporting platforms should be developed, ensuring confidentiality and protecting victims from blame. Rapid response protocols should include legal aid, counselling, and safe reporting spaces. Victim-centred approaches, where survivors play a key role in decision-making, must be strengthened. Dedicated cybercrime units focusing on TFGBV should be established within law enforcement agencies. To prevent case withdrawals under pressure, victims should be provided with legal assistance, counselling, financial support, and protection from intimidation, ensuring they feel safe to pursue justice.

Holding Digital Platforms Accountable: Stronger content moderation policies and efficient reporting mechanisms must be advocated for on social media and digital platforms. Collaborating with tech companies is essential to establish clear procedures for removing harmful content and obtaining digital evidence for legal cases. Additionally, pushing for robust data protection laws is crucial to prevent online harassment, doxxing, and identity theft, ensuring safer digital spaces for all users.

Cultural and Institutional Reforms: Challenging patriarchal norms and traditional biases that perpetuate TFGBV requires targeted awareness and advocacy campaigns. Gender-sensitivity training should be promoted for government agencies, law enforcement, and media professionals to foster a more inclusive approach. Media outlets must be encouraged to report responsibly on TFGBV, emphasizing perpetrator accountability and steering clear of victim-blaming.

Special Protection for Marginalized Groups: Address the intersectionality of TFGBV by designing targeted interventions for LGBTQIA+ individuals, indigenous women, and other marginalized groups. Improve data collection on gender-diverse communities to develop evidence-based policies and programs. Engage local women’s rights organizations, LGBTQIA+ groups, and community leaders in crafting inclusive digital safety strategies.

Strengthening Digital Defenders and Advocacy Networks: To address the intersectionality of TFGBV, targeted interventions must be designed for LGBTQIA+ individuals, indigenous women, and other marginalized groups. Improving data collection on gender-diverse communities is crucial for developing evidence-based policies and programs. Engaging local women’s rights organizations, LGBTQIA+ groups, and community leaders in crafting inclusive digital safety strategies will ensure that no one is left behind in the fight against online violence.

Immediate Response Protocols for Crisis Situations: Clear emergency response mechanisms must be developed for online harassment cases that could escalate to offline violence. Coordination between law enforcement, mental health professionals, social services, and digital platforms is essential for swift intervention. National helplines dedicated to assisting victims of TFGBV should be set up, ensuring immediate support and action for those in need.

Combating TFGBV is Crucial for SDGs

Human rights must be promoted, protected, respected, and enjoyed in the digital space just as they are in the offline world. It is essential to address the specific needs of individuals in the digital realm to ensure that no one is left behind. Combating TFGBV is integral to achieving key SDGs, particularly SDG 5, which focuses on achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls, and SDG 16, which emphasizes the importance of peace, justice, and strong institutions.

The fight against TFGBV directly contributes to the fulfilment of several SDG targets. Target 1.4, which seeks to ensure that all men and women, especially the poor and vulnerable, have equal access to appropriate technology, is closely tied to addressing online violence. By creating a safer digital environment, we can ensure that everyone can use technology without fear of abuse or discrimination.

Target 5.b calls for enhancing the use of technology, particularly Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), to promote the empowerment of women. Combating TFGBV is crucial to enabling women to fully engage with and benefit from technological advancements, particularly in spaces where they have historically been marginalized.

Target 9.c aims to significantly increase access to ICTs and strive for universal, affordable internet access in least developed countries. As more people in Bangladesh and similar regions gain access to the internet, it becomes even more important to address the risks of TFGBV and ensure that technology serves as an empowering tool, rather than a means of harm.

By addressing the issue of TFGBV, we not only safeguard women’s rights but also contribute to the broader vision of achieving a fairer, safer, and more inclusive digital world for all, aligning with the global commitment to the SDGs.

TFGBV also significantly impacts SDG 16, which focuses on promoting peace, justice, and strengthening institutions. One of its key targets is to reduce all forms of violence, including in digital spaces, and ensure access to information while safeguarding freedoms. Digital harassment undermines women’s ability to exercise their rights, particularly their right to free expression, silencing activists, journalists, and human rights defenders. This not only limits women’s participation in democratic processes but also harms society by restricting diverse voices. In summary, addressing Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence is not just about protecting women; it is about upholding human rights, ensuring inclusive participation, and fostering just and peaceful societies.

Concluding Remarks

Throughout this paper, it has become evident that TFGBV in Bangladesh has reached critical levels, rooted deeply in gender disparities that are amplified by the anonymity afforded by the digital realm. This form of violence not only silences women, especially those who are activists, journalists, and human rights defenders, but it also obstructs their ability to participate fully in the digital world and contribute meaningfully to democratic processes.

The cases explored herein highlight the urgent necessity for comprehensive legal frameworks, robust enforcement mechanisms, and strengthened support systems for victims. While existing legal provisions mark a positive step, substantial gaps persist in addressing the nuanced challenges posed by digital violence. Combating TFGBV requires more than just policy reform; it demands cultural and institutional transformations that challenge patriarchal norms and foster gender sensitivity across all societal sectors. Furthermore, empowering women through digital literacy and equipping law enforcement with the tools to tackle digital crimes are critical elements in the solution.

Tackling TFGBV not only safeguards women’s rights but also contributes to the global pursuit of the SDGs. It is directly aligned with SDG 5 on gender equality and SDG 16 on peace, justice, and strong institutions, emphasising the need for a safe, inclusive, and accountable digital environment for all. It is imperative that we take immediate and concerted action to build a digital world free from violence and discrimination, where women can flourish and fully exercise their rights.

[1] https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/TFGBV_Brochure-1000×560.pdf

[2] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/understanding-nuances-technology-facilitated-violence-carol-ndosi/ [Author: Carol Ndosi, Tanzania-based feminist activist, digital rights activist]

[3] https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/women-still-lag-mobile-ownership-internet-adoption-3613001

[4] https://www.jugantor.com/tp-lastpage/860243

[5] https://www.thedailystar.net/weekend-read/news/womens-role-toppling-the-govt-3679151

[6] https://www.facebook.com/FIC.Bangladesh

[7] https://www.bbc.com/bengali/articles/c51ejgq45xlo

[8] https://bangla.bdnews24.com/bangladesh/127f15ec9604

[9] https://www.blast.org.bd/content/publications/The-Children-Act%202013.pdf